Oceania Regional meeting highlights

Indigenous leadership in Forest Stewardship

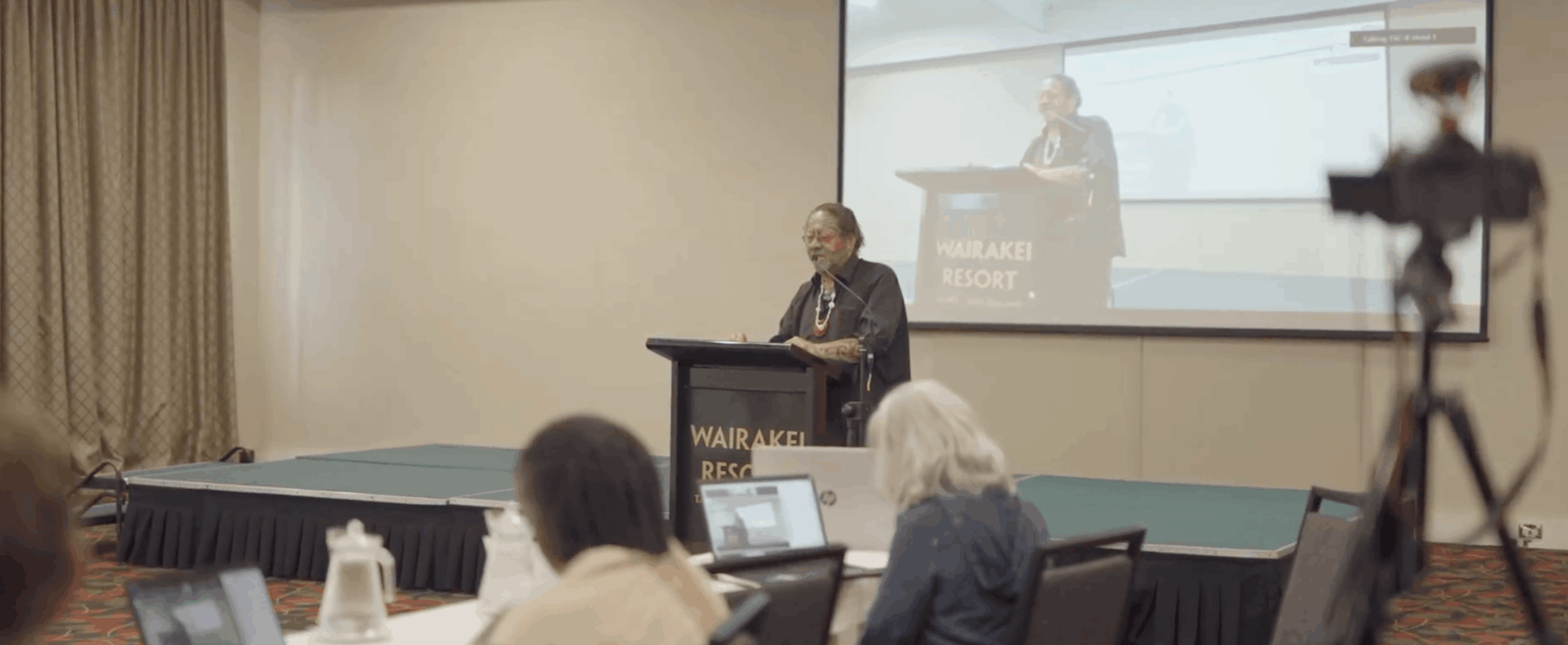

In January 2025, leaders, experts, and Indigenous representatives from across Oceania and beyond gathered for an important regional meeting focused on the future of forest stewardship. The event created a powerful space for collaboration, learning, and dialogue. At its heart was a shared goal: to strengthen Indigenous leadership and ensure that traditional knowledge stands alongside Western science in shaping sustainable forest management.

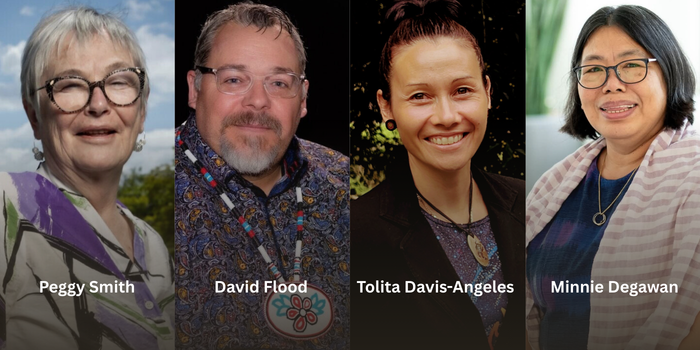

The meeting highlighted the role of the Forest Stewardship Council in the region, the work of the FSC Indigenous Foundation, and the importance of the Permanent Indigenous Peoples Committee (PIPC) in advancing Indigenous rights within global forest governance. A key outcome of the gathering was the nomination and election of new PIPC representatives for Oceania, ensuring continued Indigenous representation in FSC’s decision-making processes.

Above all, the meeting reaffirmed a strong commitment to cultural respect, Free, Prior, and Informed Consent FPIC, and inclusive leadership.

Day 1: Foundations of Indigenous Leadership in Forest Stewardship

Day 1 began with a traditional Pōwhiri welcome ceremony and Karakia prayer, grounding the meeting in respect for Māori customs and Indigenous traditions. This opening set the tone for meaningful and culturally respectful dialogue.

Leaders from FSC International, the FSC Indigenous Foundation, and the PIPC shared opening remarks, emphasizing the importance of Indigenous leadership and FPIC in forest governance.

Participants were introduced to the FSC system and its work in Oceania, including certification processes and regional priorities. The role of the Permanent Indigenous Peoples Committee PIPC was highlighted, particularly its responsibility to advise the FSC Board of Directors on Indigenous rights and to advance an Indigenous Peoples Agenda within FSC.

The FSC Indigenous Foundation presented its mission to uphold Indigenous rights, strengthen forest stewardship, and promote Indigenous-led solutions.

A closing Karakia brought the first day to an end.

Day 1 video summary:

Day 2: Strengthening Collaboration and Engagement

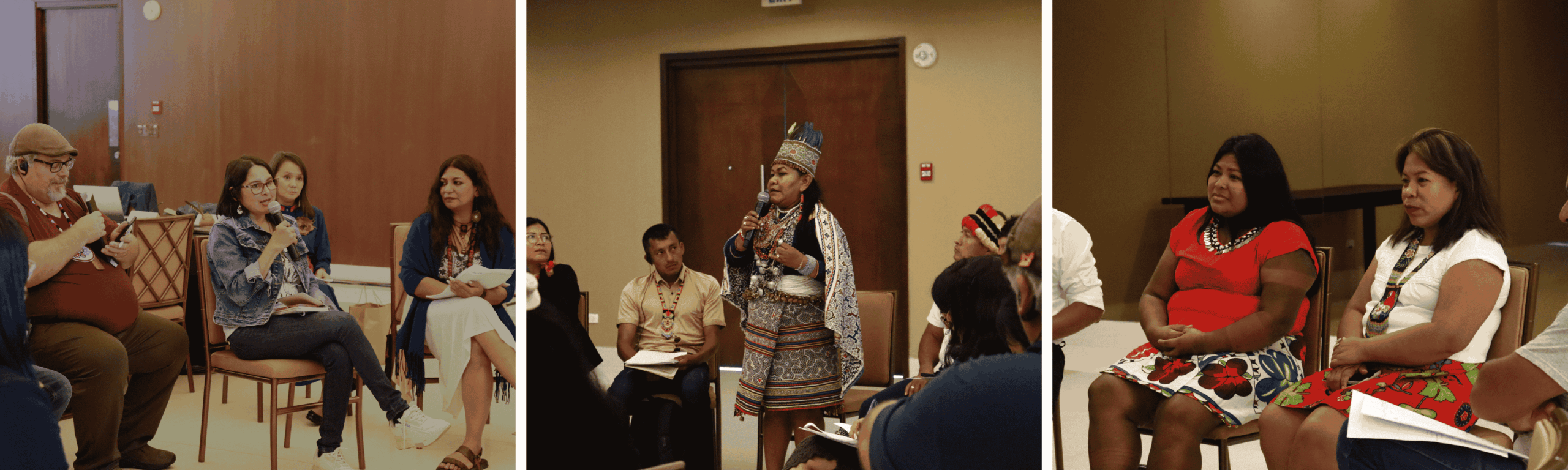

Day 2 opened with a Karakia and focused on action, collaboration, and strengthening Indigenous participation.

Interactive sessions encouraged open dialogue and exchange of ideas. Speakers from New Zealand, Latin America, and other regions shared experiences on Indigenous leadership in forestry and inclusive forest strategies. Participants explored practical ways to strengthen regional cooperation and ensure Indigenous voices are fully integrated into FSC governance.

A key discussion centered on aligning regional strategies with FSC’s global priorities, reinforcing Indigenous rights, and integrating traditional ecological knowledge into ecosystem services and sustainable forest management.

One of the most important moments of the meeting was the nomination and election of new PIPC representatives for Oceania. Through a transparent and culturally respectful process, Te Ngaehe Wanikau was selected as the Principal Representative, and Tolita Davis as the Alternate Representative.

The meeting closed with a final Karakia, marking the end of two impactful days.

Day 2 video summary:

Day 3 Visit to TE POU O HINETAPEKA

On day 3, a visit to Te Pou o Hinetapeka was made.

Day 3 video summary:

Looking Ahead

This regional meeting was more than a gathering. It was a transformative step toward stronger Indigenous leadership in forest stewardship. By bringing together traditional knowledge and modern systems, the participants reinforced a shared vision: forests are not only resources, but living landscapes deeply connected to culture, identity, and future generations.