The Forest is Our Relative:

Menominee Stewardship Shows the Power of Indigenous Voices in Forestry

Voices of the Forest

Forests are more than ecosystems; they are memory, medicine, and home. As part of our Voices of the Land campaign, we spotlight the Menominee people’s centuries-old stewardship as a powerful testament to Indigenous leadership in shaping a just and living future. This story is not only about sustainable forestry, but it’s about sovereignty, intergenerational knowledge, and the unbreakable bond between Indigenous People and Mother Earth.

In April 2025, during Earth Week in Milwaukee, two Indigenous leaders from Canada, Tyler Bellis (Council of the Haida Nation) and David Flood (Ojibway, Treaty No. 9, and North America/Canada representative to the FSC Permanent Indigenous Peoples Committee), stood alongside Satnam Manhas of the FSC Indigenous Foundation and the Menominee people to celebrate a shared vision of forest stewardship. The event honored the FSC Leadership Award given to Menominee Tribal Enterprises (MTE) and the Milwaukee School of Engineering for The Giving Forest Game, a digital learning tool rooted in Menominee forest values.

But the deeper story is what happens daily in the Menominee forest: a practice of land management grounded in story, ceremony, and sovereignty.

A Living Forest, A Living Culture

In Wisconsin, the Menominee manage 230,000 acres of ancestral forest. Their philosophy, rooted in Chief Oshkosh’s 1850s guidance, “What’s best for the forest, then the people, and lastly, profit,” continues to guide MTE. Only a small fraction of the forest’s potential yield is harvested, with decisions made through both GIS mapping and cultural knowledge.

The visiting delegation toured MTE’s forest and operations, hosted by Marketing Specialist Nels B. Huse, and met with key leaders, including CEO Jennifer Peters, Sawmill Manager John Awonohopay, and Forest Manager Ronald Waukau, Sr. As they travelled from Chicago to Menominee territory, the contrast was stark; the Menominee forest stood out as the first stretch of intact, biodiverse, and actively managed forest the delegation encountered.

Nearly all MTE workers are Menominee. As Ronald Waukau Sr. noted, “We don’t use cookie-cutter prescriptions, we do what’s best for the resource.” MTE’s marketing Specialist Nels B. Huse added, “We can almost tell you the stump your product comes from. FSC helps us track that. Our customers care, and so does our community.”

Restoring Forests and Culture with Fire

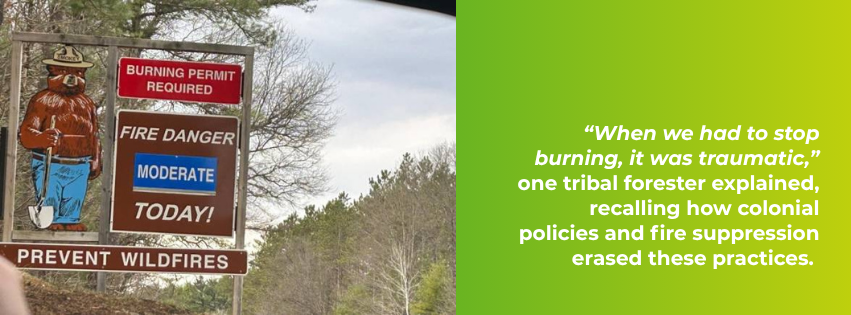

One of the most powerful expressions of Menominee stewardship is the reintroduction of controlled burns, reviving a practice once banned through colonial policies. For generations, fire was used to sustain ecosystems, food sources, and ceremony. “When we had to stop burning, it was traumatic,” one tribal forester explained, recalling how colonial policies and fire suppression erased these practices. “Smokey Bear showed up and we lost the connection. But we’re bringing it back.”

Menominee staff are combining science with tradition, analyzing historical survey notes and fire-scarred stumps to guide prescribed burns. These burns range from small 10-acre patches to areas over 200 acres, regenerating traditional foods and medicines. “We burned one area and tribal members came out to pick berries,” Ronald shared. “That’s the kind of outcome we want.”

Forest as Teacher, Forest as Healer

For the Menominee, fire is not just ecological, it’s cultural healing. It brings back blueberries, birch bark, and healing teas. One community member said, “I used to harvest for profit. Now I just do it for myself.” Younger generations are becoming more culturally awake, reconnecting with land-based knowledge. “The forest is not something we own. It’s something we belong to,” a staff member reflected.

Forestry as Sovereignty

MTE employs over 140 full-time staff, 95% of them tribal members, and supports 8–9 contract logging crews. It’s a major economic driver, but also a symbol of sovereignty. “We’re managing for food, medicine, and the connection between people and place,” said one forester.

Yet, challenges remain. Regulatory constraints make it difficult for families to engage in cultural burning. “Burning today is like a military operation,” someone noted. Still, the Menominee continue, finding ways to balance compliance and cultural rights.

As mill manager John Awonohopay put it: “The forest isn’t just an economic asset, it’s a living classroom and medicine cabinet. Visitors come in and say, ‘I can see 20 medicines just looking out the window.’”

Reflections Across Territories

For David Flood, the visit was personal. A Treaty Indian who lived disconnected from his homelands for 30 years, he said, “My hope is to live the next 30 years in service to my homelands until I too become an ancestor.”

Tyler Bellis, visiting just weeks after the Haida Nation signed a landmark agreement affirming Haida Title, saw in Menominee forestry a living model of what it means to steward land through Indigenous law and values. “It offered a vision into action, and the need to always return to the people,” he reflected.

Satnam Manhas summarized it best: “Unlike extractive economic systems that lead to scarcity, this is a regenerative model rooted in action, where abundance supports land, species, and people.”

From left to right: Satnam Manhas, David Flood, and Tyler Bellis

The Menominee story is a powerful reflection of Indigenous Knowledge Systems in action, knowledge that is rooted in land, passed down through generations, and lived through practice. From controlled burns to food sovereignty, from cultural mapping to community-centered forestry, these systems offer holistic approaches that integrate ecology, economy, and spirituality. In a world facing climate collapse and biodiversity loss, Indigenous Knowledge Systems are not alternatives, they are essential.